Middle Eastern MythologiesThe Gilgamesh Epic |

What is the plot of the Gilgamesh Epic? |

The epic opens with an introduction to King Gilgamesh of Uruk, known for having built the city’s famous walls and for having written tales of his many adventure on tablets. Although Gilgamesh is praised, a major flaw becomes evident even within the first tablet when we learn that the king displays great human arrogance by tyrannizing his people, even demanding conjugal rights to brides. The people petition Anu, who instructs Aruru, a mother goddess, to find a way of tempering Gilgamesh’s power. She creates the bestial Enkidu, who eats plants of the fields and frees animals caught in hunters’ traps. When Gilgamesh is informed of Enkidu’s presence, he sends out a beautiful prostitute, Samhat, to tame Enkidu. Enkidu is somewhat humanized and, in effect, tamed after six days and seven nights of lovemaking. In Uruk, Gilgamesh has strange dreams involving Enkidu. Ninsun, Gilgamesh’s mother, explains to the king that the dreams are about the man who will become his closest friend.

In the second tablet of the epic, Gilgamesh and Enkidu have a wrestling match, which is won with great difficulty by the king. But Gilgamesh is so impressed by Enkidu’s courage and strength that he takes him on as his primary companion. In the three tablets that follow, the deeds of the two heroes in the Cedar Forest of Enlil, guarded by Humbaba (the Sumerian Hawawa) whom they kill, are described.

In Tablet 6, we find the story of Gilgamesh’s refusal of Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna). Having returned to Uruk after his monster-killing adventure, Gilgamesh is now, in effect, a new man, cleansed of his tyrannical ways. He is approached by Ishtar, who suggests love and marriage and, by extension, fertility for himself, his city, and its agriculture and animals. Using the excuse of the tragic ends of so many of the goddess’s former lovers, Gilgamesh arrogantly refuses the great goddess. Ishtar, never having been treated in this way, has Anu send the Bull of Heaven (the natural companion of the fertility and love goddess) to attack Gilamesh and Enkidu and the people of Uruk. Hundreds are killed (perhaps a metaphor for a plague) before the two heroes manage to kill the Bull of Heaven. In an ultimate insult, Gilgamesh flings a thigh of the beast at Ishtar.

The rejection of Ishtar is strange, especially since she was the patron and city goddess of Uruk. The rites of the sacred marriage of kings and goddesses had been a foundation of Mesopotamian culture at least since the Old Sumerian period. The incident seems to suggest the same kind of movement away from a strong goddess-based religion that we have also found in the defeat of Tiamat in the Babylonian Enuma Elish.

In Tablet 7, Anu, Ea, and Shamash decide that either Enkidu or Gilgamesh must pay with his life for the killing of Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven.

In Tablet 8, Enkidu dies and is mourned emotionally by Gilgamesh.

Tablet 9 contains the first part of what is, in effect, an archetypal heroic descent into the Underworld. This is a journey marked by Gilgamesh’s fear of death and by a danger-filled journey. First, Gilgamesh must convince the horrible scorpion people to allow him passage through a long, dark tunnel. Then he has a relationship with the beautiful Siduri in her jeweled garden, reminding us of later dalliances in Homer’s Odyssey between the Greek hero and Calypso and Circe, and of the Roman Aeneas’s love affair in the Aeneid with Dido. These are all seen by their epic authors as temptations by women who, through sex, would undermine the necessary mission of a patriarchal hero. Like Ishtar, Siduri is a force that must be overcome. Reluctantly, again like Circe in the Odyssey, Siduri finally helps Gilgamesh on his way.

Tablet 10 finds Gilgamesh being ferried by Urshanabi across the Waters of Death to the ancient Mesopotamian Noah figure, Utnapishtim (Sumerian Ziusudra). Gilgamesh is in search of eternal life and, perhaps, of new life for Enkidu. Utnapishtim reminds his visitor that only the gods control life and death.

Tablet 11 contains the flood myth, which, as many scholars have noted, is remarkably similar to Noah’s flood described in the book of Genesis in the Bible. When Gilgamesh asks Utnapishtim to explain how he has achieved eternal life, the old flood hero answers by reciting the story of the deluge.

Ea had come to Utnapishtim and his wife in Shuruppak to warn them that a flood was about to destroy humanity. If they built a boat, for which Ea provided the measurements, Utnapishtim and his family would be spared. Utnapishtim did as he was instructed and filled the boat with valuables, his own family, and representatives of all species. A huge storm ensued and waters flooded the earth. When after seven days, the storm finally abated, the ship came aground on Mount Nisir. After another week had passed, Utnapishtim released a dove, hoping it would find land, but it returned, unsuccessful, to the ship. The same scenario followed a swallow’s release. When a raven was sent out, however, it did not come back, and Utnapishtim realized that the flood was over. He gave thanks to the gods and made offerings. The mother goddess promised him care and Enlil granted him the ultimate gift of eternal life.

Gilgamesh, too, longs for eternal life, but Utnapishtim tests his ability to achieve it by setting a test. He challenges the hero to avoid sleep for six days and seven nights. The exhausted Gilgamesh agrees to the test but immediately falls asleep. Utnapishtim’s wife bakes a loaf of bread each day that Gilgamesh remains asleep. When the hero wakes up, he finds the now-moldy bread and accepts his limitations. As a human he has human frailties. He cannot expect eternal life. But before Gilgamesh takes his leave of Utnapishtim, the old man, at the urging of his wife, tells Gilgamesh about an underwater plant that can at least preserve youth. On his way back across the Waters of Death with the ferry man Urshanabi, the hero dives for the plant and succeeds in retrieving it, but once again, he falls asleep, and a serpent steals the plant. This is why serpents can slough off and replace old skin. In despair, Gilgamesh weeps, but he and Urshanabi go back to Uruk together. There Gilgamesh, chastened, nevertheless proudly asks the ferryman to inspect his great wall and his fine city. In a sense, the hero accepts his humanity.

A twelfth and final tablet often included is present only in an Assyrian version of the epic and is essentially a retelling of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Underworld story found in the earlier Sumerian Gilgamesh cycle.

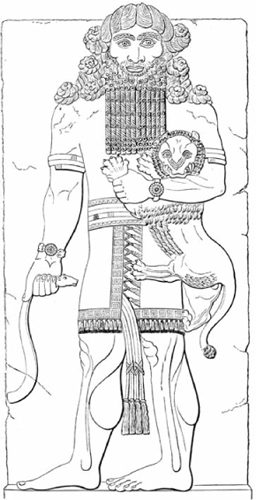

An 1876 drawing reproducing a depiction of the Babylonian hero Gilgamesh.